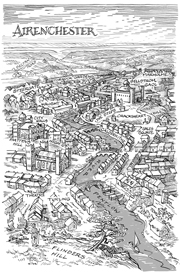

THE OLD BELLSTROM GAOL crouched above the fine city of Airenchester like a black spider on a heap of spoils. It presided over The Steps, a ramshackle pile of cramped yards and tenements teeming about rambling stairs, and glared across the River Pentlow towards Battens Hill, where the sombre courts and city halls stood. From Cracksheart Hill, the Bellstrom loomed on every prospect and was glimpsed at the end of every lane. Yet one night (a very dark night, and fiercely cold) at the failing end of 1775, the Bellstrom Gaol was no more than a dim line on the hill, pierced by the glow of banked fires behind its barred windows and one gleam of candlelight in the top chamber of its highest tower. Lady Stepney held a great entertainment at her place in town. Brilliant flambeaux flared on the cobbled drive. A row of carriages wound along the street, and the drivers sat, hunched on their high seats with their coat collars turned up, and took what cheer they could from the music and loud voices heard at the windows. The air was cold and hard and clear, like the fine lead crystal laid on the tables. Darkness gathered behind the riverside warehouses and about The Steps, but the quality of Airenchester moved in a finer medium, in the brilliance of countless flames. Mayor Shorter attended, among many worthies. He stood before a snapping fire and gallantly took the hand of any man passing. Here were the masters of Airenchester: merchants, bankers, and magistrates, its grand families in cheerful concord, takers of punch and conversation. The quality talked and fanned themselves, joined the quadrille or sat at cards, chattering and laughing, passing, curtseying, and bowing. Yet it become a little hard to catch one's breath in the press and stir of the crowd, and the hot flames of the candles were reflected in acres of plate silver, facets of crystal, gilded mirrors, brilliant threads on coats and gowns, and bright eyes. No one noticed that a little bird had slipped inside and become mazed among the chandeliers and painted arches, and desperately fluttered against a closed window. Mr. Thaddeus Grainger might have seen the sparrow, if he had raised his eyes one more time, as if casting up among the heavens for some fantastic engine that would pluck him from the company. He stood in a corner, behind a knot of animation and laughter in which he took no part. Mr. Grainger was a young gentleman of a good height, well-featured and dark. Though his coat and collar were a touch plain, he was finely dressed. He glanced up again, weary of what he found below. Indeed, there was something careless in his stance and expression. He had an excellent name (among the quality of Airenchester), a commendable fortune in property, scant ambition, a great deal of idleness, and perhaps too fine a sense of his failings and too much pride for his improvement. He shrugged and stepped forward, but before he had gone far, Lady Stepney was before him. "You are not escaping!" she exclaimed and rapped him with dire playfulness on the chest. "Should I flee such fair captivity?" he asked, smiling lazily. It was hard to make out much of Lady Stepney, besides an impression of lace and silky stuff, perfume and coiled hair (not much of it her own), dazzling jewels, and some small stretches of whitened flesh. "You won't charm me, young Grainger." Her fan fell again, as Lady Stepney made a cut that would gratify a fencing master. "You must dance again with Miss Pears. I foretell a fine match there, a prosperous match. And I think I have yet to see you pass a civil word with anyone else." "They have passed enough words with me," he retorted. "Throwsbury bores me with corn and some business concerning drainage, Grantham with hunting and dogs, and I have barely avoided Tinsdowne and a lecture on divinity." "You are a wicked man," charged Lady Stepney. "I plead innocence," he cried, with a bow. "Nonsense. I won't hear you. Take another glass at least and join Mrs. Marshall. She is desperate for a partner at piquet." "Mrs. Marshall can find an abler opponent than me." The fan recoiled, and Grainger concealed a wince, but the mist of finery that constituted Lady Stepney did not relent. "Mr. Grainger, when you get a wife, she will correct your negligent ways. We shall make you respectable." "You set this speculative wife a terrible task." "Ghastly man! Come in and speak to Miss Pears. She will be inconsolable if you pay her no more attention." "My regrets. It is very close. Some cool air will restore me." The fan made a sword-cut again and lighted on his shoulder. Grainger inclined his head minutely. "Young Massingham will attend this evening," confided Lady Stepney. "He presents rather well. His mother lately remarried a baron, you know. I hear he has an eye for Miss Pears." "He is no rival of mine," said Grainger coldly. "Fie! You wear it too lightly." "I think you are as keen to make scandals as matches, my lady." The fan twirled and touched him on the chin. "Horrid man. You don't know me at all. I shall let you go and think of you not one bit more." And with an airy turn and a lifting of the heels, Lady Stepney, gown, fan, jewels, and all, departed, leaving Thaddeus Grainger with his hand on his chin. For a moment he held this musing stance, and then, with a shake of his head, he too took his leave. • • •

THADDEUS GRAINGER descended the stairs, hat and cloak in hand. Gusts of heat and music rolled down from the open doors, but the night air cooled him, and his eyes cleared. Another party, newly arrived, four or five gentlemen, came up with heavy footfalls and loud talk. Mr. Grainger paused to let them pass and sketched a bow, a trifle unsteadily. The first to approach him was Piers Massingham. He was a year or two younger than Grainger. Handsome, though with a narrow cast of features, he was of the same idle order: apt to his pleasure but acutely conscious of his position. He crossed before Grainger, who was forced to check his motion on the stairs. "Pray, do not let me detain you," said Massingham. "Rest assured, I would by no means tarry on your account." "You are in haste," noted Massingham, standing easily and toying with his gloves. "Indeed, no," rejoined Grainger, smiling thinly without a trace of pleasure. "Mr. Grainger," said Massingham loudly, "is set on an assignation, and we have thoughtlessly delayed him." A general snigger erupted from the three behind him. "Not at all. I give you good night." "Of course. Kempe, don't dither. Step aside and let Grainger pass." And so the one went down and the many came up; the one down into the sharp, still night, to pass the rows of carriages and along the road, the many up into the whirl and merriment, the rousing music and the staring lights. • • •

|

Top Five Books, LLC,

is a Chicago-based independent publisher dedicated to publishing only the finest fiction, timeless classics, and select nonfiction.

is a Chicago-based independent publisher dedicated to publishing only the finest fiction, timeless classics, and select nonfiction.

© Top Five Books, LLC. All rights reserved.